KNOT Magazine

Fall Issue 2022

"Coconut Boys" and "Fallbrook is a Small Town,"

by Kit Bacon-Gressitt

Mr. Phan stands and faces the passengers, his small frame mostly hidden by his seat back, a microphone in his hand. He blinks through thick, round glasses, with their broken tortious shell frame. Nodding in one direction, his eyes grow large; in another, bisected. On his periphery, rice fields blur by, water buffalos, shrines sending the smoke of lemon grass incense to ancestors.

Mr. Phan responds to a question. “No, no wifi on bus. You no need wifi. Wife you need. Without wife, you die. Without wifi, you live. No need wifi.” He sits.

The U.S. war veterans chuckle. Their wives, too. They shuffle their daypacks, water bottles, emergency TP, and cameras, ready to aim and fire. The wives wonder quietly if this trip will quell their spouses’ nightmares. The vets don’t talk about why they have come.

The bus rolls on, its engine humming to memories. Battle maps and stories meander from one seat to the next.

Mr. Phan stands again, says he will explain what happened to the South Vietnamese after the U.S. left and the war against the communists was lost. “There are three groups,” he says. “First group, ARVN soldiers, they are ordered to report to local police stations. They are afraid to go, but they go. They are sent to reeducation camps. Can you guess for how long? One year, two years, five years, ten years, more. Depends on rank. Officers spend many years. Some do not return, ever.”

The veterans, in their sixties and seventies, lean across the bus aisle, laughing through their own stories. “It was Typhoon Con 1,” one of them says. “That meant wearing a helmet at all times—even to the shitter. I had a first lieutenant who didn’t want to wear his helmet. Refused to wear it. I told him to keep that fucker on his head. So the next day he strutted out for morning ablutions with nothing on but his goddamn helmet.” “Yeh,” another says, “I hadn’t had R&R in months—one thing or another. The colonel found out. Ordered me to meet my wife in Hawaii. Then the typhoon hit and local travel was shutdown. The colonel said, ‘You’re going anyway. Your wife is waiting for you,’ he said, ‘the typhoon be damned.’ He even sent his own driver to get me to the transport plane. Now, that’s a lesson in leadership.”

“Second group,” Mr. Phan continues, “wealthy people. What you think happens to them? NVA goes through their houses, their businesses, takes everything valuable. Takes their houses. Sends them to farms to work for people they rob with their privilege. Man owns jewelry store. Has black chain on door. Soldier scratches chain. Is gold. All man’s jewelry made into chain. Soldier takes gold. Man goes to reeducation camp.”

The veterans huddle closer now, standing in the aisle, half again as tall as Mr. Phan and twice as loud. They support each other on the rocking bus, swaying to the rhythm, one memory segueing to the next, vying with Mr. Phan’s microphone. “That major,” one vet looks ready to spit, “he was a jerk. He insisted on going on patrol. His gunny told him he shouldn’t be doing that, but he wouldn’t listen. Some guys just hope they’ll be heroic. He was one of those guys who wanted the glory. He stood up at the wrong time and took one in the face. He had it coming. Guy was a jerk.”

“Third group,” Mr. Phan says, “group three is regular people. Like my family.” He pauses, looks for passenger eyes on him, nods at the few he finds. “I tell you what happens to us. I am twelve. My father is teacher. He and my brother stay in our house in Saigon. My mother and I go to our coconut farm in Me Kong Delta. Small farm. We grow coconuts, but we are not able to sell them. They go to government. We cannot sell coconuts, we cannot buy rice. Government gives us too little. We need rice to live. So we go at night, we take our coconuts and sell on what you call ‘black market.’ Big risk. Very dangerous. We sell them so we can eat. We are afraid. But we must eat. We are hungry always.”

The veterans shift. Some of their weary knees can’t take all the bumping. Some have guts grown large, their accumulated years throwing them off balance. A few are slim, as upright as in their youth. Their stories continue while they pass the Que Son Mountains and Antenna Valley. “That’s where that SPIE went bad.” “What’s that?” a wife asks. “SPIE, special purpose insertion and extraction. It was called ‘Thunder Chicken.’ Eighteen November 1970 at sixteen-thirty,” a vet says. “It was a war cloud,” says another. “Two hundred feet visibility. The helos came to extract a unit. The birds flew around the long way, fifty feet above the river from the north and then up Antenna Valley. One bird flew up the creek, and a team led them in by sound, by radio. Picked up seven men, hanging on the rope, a cargo harness. The bird turned the wrong way. We lost fourteen Marines and one Navy corpsman.”

Mr. Phan carries on. “My mother,” he says, “she takes me to visit my aunt and cousin, Hung. Hung is boy, my age. He wants to leave Viet Nam, to escape. Says I come with him. I am not certain. I am afraid. I do not want to leave my mother. She says I decide. I think I leave. I think I stay. Hung says, ‘Come with me.’ But I do not know what to do. I worry. I decide no. Hung leaves, alone. Very, very dangerous.”

The veterans have faded to silence. Settled in their seats, they look out the windows, retrace death on maps, nod off. The wives take fuzzy photos of concrete homes guarded by ceramic dogs; sheets and clothes drying on bushes; honking motorbikes loaded with pigs, building materials, furniture, people—four on some bikes, even five; a cemetery with no bodies. It honors the village’s MIAs.

Mr. Phan persists. “A month passes,” he says. “We visit my aunt. She does not hear from Hung. We say she will hear soon. ‘He is probably on boat. He writes when he lands,’ we say. Two months, six months. We visit her again. She does not hear from Hung. She worries and worries. A year passes. We visit her. My aunt is sick. No message from Hung. She says he will return to her. More months. We visit. My aunt is dying. She sees me and sits up. ‘Hung,’ she cries, ‘you are back, my son!’ We never hear from Hung. He is gone. Maybe boat sinks. We never know. My aunt dies. My mother says, ‘You must go back to Sai Gon. Get education. Become man. You cannot be coconut boy forever,’ she says. I go, study to be English teacher. Must learn communist slogans in English. Now, today, I here with you.”

Mr. Phan bows his head.

A vet mumbles to a window, maybe to a dream, “They wouldn’t have what they have today if we didn’t do what we did here.”

Mr. Phan removes his glasses. Wipes his eyes. Returns the glasses. Smiles. “Now we go to Hoi An,” he says. “Town on coast. Very nice. Old shipping port. Good shopping.”

[end]

"Fallbrook is a Small Town"

Fallbrook is a small town, best known, if at all, for avocados and racism. I've long thought the combination compelling, almost cosmic. Does one somehow balance the other? Perhaps bigotry and a misunderstood fruit are not too heavy a burden for my little community to bear. Indeed, over the years I’ve learned to gently challenge those who remark on “the illegals, the liberals, and the fags,” egged on by our history of a white-supremacist-in-residence, Tom Metzger. Oh, the many times in the grocery checkout line I’ve witnessed the classic Fallbrook line, “I’m not a racist, but— ” My restraint is a remnant, perhaps, of my dear, sweet mother’s advice to love the unlovely or, more likely, it’s a function of my adamant desire to avoid the incarceration inherent in taking a felonious poke at those who annoy me. And if I annoy them? Well, so be it.

As for the avocados—our testicle fruit—how delicious that the Nahuas so colorfully named them. They are quite yummy, a dreamy palatal delight. They're particularly fine tenderly mashed into buttered brown rice, with fresh cilantro and a squirt of tree-ripened lime picked just before dinner.

Whatever our sins, though—venial, mortal, imagined—our avocados temper us, forcing us to contemplate nature, our landscape’s and our own, as we slowly trail packinghouse flatbeds and growers’ trucks stacked high with Fallbrook’s produce, as we hug the winding double line in fuel-greedy cars eager to pass caravans of bicycling pickers bowed with age and occupation and toting lunch pails filled with a hope the more privileged commuters don’t see. The harvest and the harvesters, they tether us to the earth, to our so-subtle seasons, to our odd and uncalculated blend of people and proclivities, to the terms of our town.

Our fearless leaders refer to this bucolic burg alternately as “Fallbrook the Friendly Village” and “The Avocado Capital of the World.” I’ve long wondered if the former nomenclature is hopeful atonement for the rancid reputation born of playing home base to celebrated racists for so many years. I've never asked, though—assumed I wouldn't get a straight answer. And now the latter title has fallen into the realm of wishful thinking as not-so-free trade, cross-border trucking, and Mexico's cheap water and labor compete with our growers—even as we rely on Mexico's underpaid workforce here. The juxtaposition ought not be lost on those who hate and hire them.

Nonetheless, like towns across the country, Fallbrook struggles to maintain a local economy. We are torn between sustaining and creating a character that will thrive, while old-timers slowly drag their stories to their graves. Our retail entrepreneurs recycle storefronts as fluidly as Rosita’s frijoles refritos travel their route. Movers and shakers strive to distinguish our town from the urban sprawl that threatens—from just over the pass—by promoting Fallbrook to busloads of day-trippers—from just over the pass. And they plot, sipping martinis as dry as the desert they try to fend off, to redirect traffic around the Spanish signage that propagates North Main.

For all its folly, though, Fallbrook does attract an olio of immigrants: families escaping the miasma of urban dwelling, laborers seeking a safe place in the world, maturing professionals who aspire to weekend farming, artists in search of vision, the occasional recluse who wants nothing more than to hide behind our toxic oleanders. Folks move here and wait for the magic of rural living to happen to them. Those who find it, merge into the orderly landscape of our groves.

Others struggle with the adjustment. They strive to be welcomed at hoedowns and classic car parades, to which some drive in snazzy Jaguars, Hummers, Bentleys. They lust for the social embrace of over-the-backyard-fence chats and farm-store debates of the virtues of stomping snails versus poisoning them, but they don’t want that nasty muck on their Smith and Hawken’s garden clogs. They wait to be embraced as personalities of import, shopping at Major Market in their studiously understated attire, bemoaning the limited selection of lox and foie gras and caviar. They yearn to receive the charms of the natives: the sassy waitress who knows what her regulars will order and calls them by their first names; the grove manager who does their farming for them with a smile and calls them all “Nitwits!” for their failure to comprehend root rot; the pie shop owner who calls everyone “Sweetie”—and isn’t he one, they whisper.

And when the magic does not happen to them in urban timing, our unrooted transplants want to call it quits, bemoaning the void of finery, the dearth of fine dining, the lack of a sense of community.

But come on, now. No sense of community? They need only open their eyes a little wider, peer between the leaves of our avocado and persimmon trees, our macadamias and lychees and blood oranges. It’s there, if they choose to see it.

There’s the tamale man from Mexico City. He comes to the door, singing a very competent Puccini and selling homemade tamales his wife rolls in cornhusks and love.

And there are the quite handsome soccer moms. They dodge murderously competitive parents, survive the teen years of muffled conversations and loud whining about “this boring redneck bitch of a town,” and finally shuttle their kids off to college, regaining their own independence and the right to have utterly uncensored fun.

And the entrenched Marines, well retired, seeking peace and quiet and lucrative contracts in distant wars. When they’re home, they can be counted on to draw their weapons at the slightest hope of an altercation.

And the writers of letters to the local paper. Aren’t they a caterwaul. They define their success by the volume of vitriol that follows their weekly declarations, published alongside the names of every Fallbrook child the paper can possibly squeeze in, whether or not any of them are newsworthy. They are our progeny. They can kick a ball and pick their noses simultaneously. That is news enough.

And the bountiful Twelve Steppers. We have a flavor for whatever ails you. They compete for free meeting space and replace anonymity with friendly nods at the market, the gas station, the post office, the orthodontist, concerts on the green, the feed store. They are pervasive. They are us.

And the Mexicans, many of whom actually aren’t. Rather, they hail from Guatemala, El Salvador, Nicaragua, lands that cannot feed their babes, riddled with gangs that threaten to annihilate them. They slowly learn this pueblo is also theirs, despite the conquerors’ resistance, while their children eat the avocados they pick. They play Red Rover at the border, marry the locals, take to using ketchup, learn to dodge a different type of gang here, the more insidious political variety.

And the denizens of the VFW where boilermakers are de rigueur and Old Glory Red lip prints adorn the rims of the widows’ shot glasses.

And the folks at the convenience store around the corner. They look askance as I crawl in for 20 ounces of caffeine, growling and grumpy. I tell them not to talk to me; it's too early. They laugh, tell the latest joke about the damn liberals, and tell me to have a good day. If only they knew.

We are a hoot, I admit, although a few of us do take ourselves and our religion a smidgeon too seriously.

Still, no sense of community? Ha! Fallbrook is awash in community, as deep and as raging as the floodwaters of the Santa Margarita—outlandish, annoying, creative, eccentric, prejudiced, diverse and delightful community. This is our town. Here, where people who love to hate are surely outnumbered by those who simply love. Here, where the businesses can barely keep their doors open (if we'd all just shop Fallbrook first!). Here, where the memory of Tom Metzger is fading, and every child knows the avocado is a fruit.

[end]

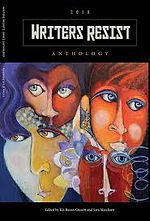

Kit-Bacon Gressitt is the publisher of Writers Resist, an online literary journal, and a contributing editor of Writers Resist: The Anthology 2018 (Running Wild Press, 2018). She is also a Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies lecturer at California State University, San Marcos. K-B can be reached at kbgressitt@gmail.com.